Artículo de investigación.

Cyberactivism and media accountability: right to communication in facebook group “movement for the preservation of tve/fm cultura”

Ciberactivismo y responsabilidad mediatica: derocho a la comunicación del grupo de facebook “movimiento para la preservación de tve/fm cultura”

Ciberativismo e responsabilidade da mídia: direito à comunicação pelo grupo do facebook “movimento para a preservação da tve/fm cultura”

Ângela Lovato Dellazzana

lovato.angela@gmail.com

PhD in Social Communication, PUCRS- Professor at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul – UFRGS.

Ana Luiza Coiro Moraes

anacoiro@gmail.com

Professor of the Postgraduate Program in Communication at the Cásper

Líbero College (FCL), São Paulo, Brazil. PhD in Social Communication from the Pontifical

Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul

(PUCRS), Post-doctorate in

ISSN: 1692-5688 | eISSN: 2590-8057

Recibido: 27 de julio de 2018

Aceptado: 6 de junio de 2019

Publicado: 12 de diciembre de 2019

Cómo citar: Lovato, A., & Coiro, A. (2019). Cyberactivism and media accountability: right to communication in facebook group “movement for the preservation of tve/fm cultura. MEDIACIONES, 15(23), 107-130. https://doi.org/10.26620/uniminuto.mediaciones.15.23.2019.107-130.

Conflicto de intereses: los autores han declarado que no existen intereses en competencia.

Abstract

The extinction of Fundação Piratini (a public foundation comprising of a public television network, TVE, and a public radio service, FM Cultura), in Porto Alegre, Brazil, which was approved by the State Legislative Council, undermines the right to communication of the people of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. This extinction, which was part of the “reduction of the State” package of Governor Ivo Sartori (PMDB), forced people from various sections of the society to create actions of control over the government and the legislative power. In this paper, we discuss cyberactivism promoted by the Facebook group “Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura”, which was created on January 29, 2015. Our research hypothesis is that through cyberactivism this group promotes accountability by divulging information that is not being broadcast or debated by either the private media or the public broadcasters, which have been shot down by administrators appointed by the government that proposed its extinction.

Keywords: cyberactivism, right to communication, acounability, facebook group.

Resumen

La extinción de la Fundação Piratini (una fundación pública compuesta por una red de televisión pública, TVE y un servicio de radio público, FM Cultura), en Porto Alegre, Brasil, aprobada por el Consejo Legislativo del Estado, socava el derecho a la comunicación de las persona del Estado de Rio Grande del Sur. Esta extinción, que fue parte del paquete de “Reducción del Estado” del gobernador Ivo Sartori (PMDB), obligó a personas de diversos sectores de la sociedad a crear acciones de control sobre el gobierno y el poder legislativo. En este artículo, discutimos el ciberactivismo promovido por el grupo de Facebook “Movimiento para la Preservación de TVE/ FM Cultura”, creado el 29 de enero de 2015. Nuestra hipótesis de investigación es que a través del ciberactivismo este grupo promueve la rendición de cuentas mediante la divulgación de información que no está siendo transmitida o debatida por los medios privados o las emisoras públicas, que han sido derribados por administradores designados por el mismo gobierno que propuso su extinción.

Palabras Clave: ciberactivismo, derecho a la comunicación, responsabilidad, grupo de Facebook.

Resumo

A extinção da Fundação Piratini (uma fundação pública composta por uma rede de televisão pública, TVE; e um serviço de rádio pública, FM Cultural) localizda em Porto Alegre, Brasil, que foi aprovada pelo Conselho Legislativo Estadual, mina o direito à comunicação de pesoas no estado do Rio Grande do Sul. Essa extinção, que fazia parte do pacote de “redução do estado” do governador Ivo Sartori (PMDB), forzou à população de vários setores da sociedade a criar ações de controle sobre o governo e o poder legislativo. Neste artigo, nós discutimos o ciberativismo promovido pelo grupo no facebook “Movimento para o preservação da TVE/FM cultura”, criado em 29 de Janeiro de 2015. Nossa hipótese de pesquisa é que, por meio do ciberativismo esse grupo promova a responsabilidade divulgando informações que não estavam sendo transmitidas ou debatidas pela mídia privada ou emissoras públicas que foram abatidas pelos administradores nomeados pelo governo que propôs sua extinção.

Palavras-clave: ciberativismo, direito à comunicação, responsabilidade, grupo do Facebook.

Introduction

The Brazilian constitution of 1988 prescribes three types of transmission systems that are different but complementary in nature, namely public, state, and private. Among these three, the private and state systems are easy to define, with the former being owned by profit-making companies and the latter being owned by the state to broadcast the actions of its executive, legislative, and judicial branches. But the definition of the public system is a complex one, and has led to long-standing debates, because the constitution does not elucidate this system. However, it is possible to understand the public transmission system in Brazilian context if we analyze other studies. For example, Carvalho (2016, p. 69) explains that what defines public broadcasters is “its structural condition that ideologically represents an impartial conception of defense of the general interests of society in which the State is the main vector.”

It is important to understand here that not private broadcast companies but public radio and television are those that can guarantee the right to communication because public broadcasters act in public interest, while the model of private radio broadcasting, though based on the idea of freedom of expression and defense of public interest, has roots in the market and is linked to the commercial interests of media conglomerates and their advertisers. Ramos (2005) has classified the right to communication as a “fourth-generation” right (a new social right in addition to the first-, second-, and third-generation rights, i.e., civil, political, and social rights1, respectively). Therefore, the right to communication has sought to establish itself in between commercial broadcasters (concessionaires), who have a fragile commitment toward public interest and greater commercial appeal, and public broadcasters, who are highly committed to cultural values and media accountability, i.e., inserted in the “process that invokes the objective and subjective responsibility of professionals and communication vehicles in the constitution of democratic public spaces for discussion” (Oliveira, 2005 apud Paulino, 2010, p. 37-38).

Therefore, we can say that the extinction of Fundação Piratini (a public foundation comprising of a public television network, TVE, and a public radio service, FM Cultura), which was approved by the State Legislative Council,2 undermines the right to communication of the people of the state of Rio Grande do Sul. The extinction of Fundação Piratini, which was a part of the “reduction of the State” package endorsed by Governor Ivo Sartori (PMDB), raised concerns among people who demanded actions of control over this decision of the government and the legislative power. These voices of concern led to the formation of Movimento para a Preservação da TVE/FM Cultura. In this paper we highlight how the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura (Movimento para a Preservação da TVE/FM Cultura), which is a public Facebook group created on January 29, 2015, promotes cyberactivism and preserves the right to communication. Our research hypothesis is that through cyberactivism the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/ FM Cultura group promotes accountability by disseminating information that is not being conveyed or debated either by the private media or by the public broadcast companies (TVE and FM Cultura), who were actually silenced by administrators appointed by the government that proposed their extinction.

The objective of this research is to discuss data collected quantitatively, categorizing the group’s posts and interpreting those graphically, and qualitatively examining the interview with the manager of the Facebook group “Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura,” Maíra Baumgarten.

For the purpose of this research, we articulated the concepts of Internet, digital social networks, cyberactivism, and right to communication (Levy, 1996, 1999; Recuero, 2009; Malini and Antoun, 2013; Ramos 2005) and the concepts of accountability, media, and government (ANDI, 2007; Bertrand, 2002; Maia, 2008).

The global exchange of ideas and information and the virtualization of communication are part of a process that began with the advent of writing, which allowed access and sharing of the most varied contents, both factual and fictional.

Chinese, Mayans, Sumerians, and Egyptians developed written communication 5000 years ago, at different points in history, to meet the needs of agriculture (property rights and calendar for planting and harvesting times) and trade. The Greek alphabet, which is more evolved than these early written codes, is being used even to this day, and so are the foundations of Western philosophy, especially of Plato and Aristotle, tragedies and comedies written by Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides between the fifth and sixth centuries. However, such contents have had their access deterritorialized, producing a new configuration of social space- time (Levy, 1996, 1999). Typography―the mechanical process for serial production of books―historically meant the transition from a civil process of oral tradition, when the space-time context of the emission of the messages was the same as its reception, for a dimension separated from the living context in which they were produced.

Being a virtualizing agent, the writing thus desynchronizes and delocalizes. It has given rise to a communication device in which messages are very often separated in time and space from their source of emission and thus are received out of context (Levy, 1996, p. 38, our translation).

Internet can transform normal text into hypertext, i.e., a text structured in a network that allows its simultaneous access and complementation to several users (Levy, 1996). Hypertext is also considered an effective tool for cyberactivism because its collaborative nature allows all interested people to share information, opinions, and positions simultaneously, promoting even media accountability. In current times, citizen participation is increasingly linked to use of Internet and digital social networking sites, which have worked as possibilities for people and institutions “to become content transmitters in an unlimited way and without external control (e.g., as in the traditional media), based on personal interests, needs, community interests and the public interest” (Peruzzo, 2005, p. 273). These content transmitters include community organizations and social movements as well as their debates and struggles all of which is giving voice to cyberactivism.

According to Malini and Antoun (2013), cyberactivism may be considered a digital strand of media activism, which brings together the experiences of organized social movements for the production of popular and community media as opposed to how national and transnational business conglomerates communicate. Cyberactivism, in its essence, contains the search for the expansion of civil rights, with a focus on freedom of expression. Cyberactivism promoted by the Internet, social movements, unions, parties, associations, and collectives representing minorities has populated the cyberspace with political issues (Malini and Antoun, 2013) and has culturally expanded the exercise of citizenship. According to Malini and Antoun, both forms of activism are libertarian and cyberactivism is the one that

brings together unique experiences of building digital devices, technologies and shared processes of communication, based on a process of networked social collaboration and computer technology, whose main result is the production of a world without culture intermediaries, based on free and incessant production of the common, without any levels of hierarchy that reproduce exclusively the one-all communication dynamics (Malini & Antoun, 2013, p. 21 22).

Digital social networks, such as Facebook, allow collaborative production of information, pluralization of voices, and greater circulation of information in the network and can also digitally reflect the social networks present in society (Recuero, 2009). This is what O’Reilly (2005) called the Web 2.0 architecture of participation, referring to networking sites whose structure encourages users to produce content. According to Lemos (2003), it is the liberation of the message-emission pole, the second law of cyberculture, which

[…] is nothing more than the emergence of voices and discourses previously repressed by the editing of information performed by the mass media. The release of the emission pole is present in the new forms of social relation, of information availability and in the opinion and social movement of the network (p. 9).

According to Fontcuberta (1993), the emergence of new communication technologies (cable TV, mobile phone, Internet, etc.) has brought about a major change, i.e., a specialization of audiences whose characteristics are

a. an increase in knowledge about the facts and interactive conditions of all men; b) a universally extended scientific knowledge, just as the benefits of technology are also available; c) a global public opinion that incorporates new themes and translates them into behavioral guidelines for information recipients. […] The integrative role of all these aspects is played by the means of social communication (p. 50, our translation).

Two decades later, Malini and Antoun (2013) no longer recognized this integrating role in the media and saw the formation of a networked public sphere that is autonomous in relation to media and political systems and that has freed itself from the concentrating and monopolistic broadcasting model. This means thinking of an extension of the right to communication, which would be the culmination of a struggle whose path was laid by freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of information. But as Ramos points out (2005, p. 250), acknowledging the right to communication requires understanding “that it needs to be seen as the subject of discussion and action as an essential public policy, such as public policies for health, food, sanitation, work, safety, among others.” And in the liberal ideology of market societies, under the pretext of free flow of information, what happens is not the recognition of communication as a public policy, but its appropriation as “the main guarantor and even the lever of the free market.”

Thus, while acknowledging the practice of cyberactivism in the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura, which does appropriate itself from the right to communication and conveys socially relevant information about the process of resistance and protest for the extinction of FM Cultura and TVE, we also emphasize that this does not happen outside of the media conglomerates. Cyberactivism has simply migrated into the hands of entrepreneurs such as Mark Zuckerberg, creator and owner of Facebook, whose net worth is $62.3 billion and who is the world’s eighth richest man according to a list published by Forbes (2019).

The existence of accountability is a conquest of democracy and represents the possibility of control over the actions of its rulers by society. The concept of accountability is related to responsibility because it defines the behavior expected of a person or institution and includes the mechanisms of control to ensure that this conduct is fulfilled. In this sense, an acceptable synonym for the term accountability is responsibility, a notion that can also be applied to the media, considering it passive of accountability just as governments are.

According to a report by ANDI (2007), every public policy, in a democratic regime, implies demonstration of some degree of accountability on the part of those responsible. Thus, this demonstration will be more likely to the extent that the actors responsible for exercising this control are external to the process. The report warns that it is the duty of society and especially of the media to monitor the official development of projects, their continuity, suitability, and results. Just as the media is identified as an active agent of government accountability, it can also be considered a passive agent of the media’s own accountability, as well as the state and organized citizens, who are the main agents that can use mechanisms to ensure accountability of the media in a democratic society.

Romais (2001) considers that the role of the mass media in the relationship between “laypeople” and the established power is instigating.

There is a long-standing debate in the theory of communication, summarized in the following question: does the media only disseminate opinions and points of view of the hegemonic group, or also influence the formation, expression and consumption of public opinion? It is also questioned to what extent the mass media establishes a public sphere in which citizens can debate, in a broad and democratic forum, subjects of their interest. Do they ultimately serve the means only to the interests of the market or can they be an instrument for the public good? (Romais, 2001, p. 44, our translation).

To answer Romais’s question, it is necessary to consider the nature of media in the three forms of transmission prescribed by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988: public, state, and private, which should be balanced in the role of giving the public a place for democratic debate. As a public nature, the media would be guided by the interests of the groups that represent them, emphasizing their educational and cultural role, without the pressure of advertisers. As a state nature, it would serve to publicize the actions of government and public services, and, lastly, as a private nature, the media would be, like any other private company, acting according to the logic of the market, in search of audience and advertisers, to be economically attractive. However, all the three natures of media are subject to regulations so that the service they provide is as expected because these are public concessions.

Although, regardless of the different conceptions of media power, there is a tendency toward arguing that media needs to respond to society. This debate has developed from what is known today as MAS (media accountability system). These systems involve activities such as quality control, customer service, continuing education, and self-regulation, seeking to guarantee citizens’ rights such as freedom of expression and access to information. Bertrand (2002, p. 10) believes that media accountability is the role of society since “the means of communication are themselves a political institution, which must remain independent. Discipline must necessarily be applied by non-state means.” According to Bertrand,

a MAS is any means of inciting the media to properly fulfill its role: it can be a person or group, a text or a program, a long or short process. Mediator, press council, deontology code, regular publication of self-criticism, electorate research, journalism higher education – and many others. There are more than sixty (2002, p. 10).

These mechanisms, according to ANDI (2007), are being created by social movements, through alternate and traditional media, bringing together well-known spaces such as readers’ letters, content criticism articles, and professional ethical codes. Bertrand (2002) says that media should be controlled only by message processors and consumers because neither the government nor the market can produce quality media. However, the author states that some MAS, such as ombudsmen, local press councils, internal critics and disciplinary commissions, still face obstacles to act, as they depend on the mobilization of civil society. In addition, there is hostility from entrepreneurs and industry professionals who accuse the MAS of representing threats to freedom, public relations maneuvers to mask inadequate, illegitimate, ineffective and expensive actions.

McQuail lists three general objectives of media accountability: “The more general requirement is that accountability must really protect and promote media freedom. A second goal is to prevent or limit the damage that the media can cause. Third, accountability must promote positive media benefits for society” (McQuail, 1997, p. 525, our translation). The author clarifies that to meet these objectives, the mechanisms used must be diversified, promoting a process of constant dialogue between media and society and reducing the need for arbitrary and restrictive mediations.

According to ANDI (2007, p. 8), there is no effective accountability of elected officials without freedom of expression and freedom of the press. This kind of freedom contributes to the fact that a bad government cannot be so harmful as to constitute a social control of governments through the hands of the press. The media, in turn, “is an actor relevant to contemporary society and therefore must also be accountable and subject to democratic control.”

Wolton (2004) warns that the power of the media would be an ideological view, in that it aims to put the ideal of information above all powers, when in fact, it should be placed as an opposing power. The media, and more specifically the press, would have no sense as a fourth power because by occupying such a position it would lose the alterity indispensable to its function. According to Wolton, succumbing to the notion of media as a fourth power is a seductive but dangerous notion, which questions media’s responsibilities in democratic societies.

Maia (2008) discusses the power that the media can play as the stage of the public sphere. According to Maia, the discussion should address two main issues. First, the media can only be considered a public space by giving visibility to the actors who act in it. Second, this power also depends on the degree of access to the media, of these actors, which is unequal. That is, the power of the media is subject to the ability to generate publicity of a certain media and to the degree of access conferred to the actors that act in this space.

Thus, it is possible to assert that private media are flawed as a public sphere from the point of view of democracy because it represents “a restricted access space, which is under heavy pressure from advertisers, follows impersonal rules of the market and is under increasing control of professionals of the media” (Maia, 2008, p. 180). Therefore, it is believed that public vehicles would be a way of balancing such a scenario because they would not be subject to the logic of profit and the pressure of advertisers. They would, therefore, be spaces for the true exercise of democracy, in which the plural voices of society would have the same status.

While analyzing the Facebook group Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura, we found that public perceives the failure of private media as agents of government accountability, since they denounce the lack of journalistic coverage that exposes the reality of the public workers and that pressures the government to rethink its package of changes and its consequences for society. It is important to emphasize here that the group in question was especially chosen for this study because it brought together in practice the concepts discussed here: accountability of the government and the legislative power (which voted for the extinction of foundations) and media accountability.

What this movement group in Facebook does is that it disseminates information about the extinction of TVE and FM Cultura that is not being broadcast, much less challenged, by both the private media and the public broadcasters (which are plastered by government-appointed administrators). It is therefore believed that the plurality of public broadcasters, independent of the government in office, would be the most appropriate way to maintain democratic spaces for discussion. It is interesting to point out here that TVE/FM Cultura employees did not create this group. It was rather created by a member of its audience, Maíra Baumgarten (who gave an interview for this research in order to clear her intentions about why she formed the group).

Aim of research

and interpretation of qualitative

data

Interview of the Administrator of the Group Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura

In its self-description, the group3 presents its goals: a reaction against the proposals that had not yet materialized in the extinction of the foundations and activism to the maintenance of TVE and FM Cultura. The group calls its followers from the area of culture:

The new government has only just started and is already preparing a beautiful “package of evils”, among which the proposals for the extinction of FEE, FGTS (organs for policy formulation in the area of work, employment and social development and research on social indicators) and of UERGS and TVE/FM Cultura (strategic bodies in the education and cultural sector; in the case of TVE and FM Cultura, the only ones that disseminate local cultural production more consistently). Source: ZH 01/28/15. I propose to the people who work in the area of culture, to make a strong campaign for the maintenance of TVE/ FM Cultura!! Come on guys, let’s go!!

When asked about the profiles of the already 6,623 members today, the administrator of the group clarifies that these are people who work “with culture, art, music, theater, among other areas, and that they have at FM Cultura and TVE their main (and often only) means of communication with society and publicizing their work.” Maíra Baumgarten Correa is a professor of the Social Sciences Graduate Program at the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. She is also a member of the board of directors of the Brazilian Society of Social Sciences and the adjunct secretary of the Rio Grande do Sul Regional of the Brazilian Society for the Progress of Science. When asked about the profiles of the followers, she says

There are also many listeners of FM Cultura and TVE spectators who have been feeling outraged by the policy of extinguishing these important media channels in society and who know that they will lose something that has no similar in the private sector. The employees, for sure, are also there (although they have their own page) and many people who, besides loving the Radio and the TV, are outraged by the proposal to extinguish institutions of research and communication with society, most of which have existed for 40 years or longer, and which have fulfilled the strategic role of developing research, actions and public communication in closer contact with the community of Porto Alegre and of Rio Grande.

Invoking her status as a sociologist and scholar in the area of science, technology, and culture as well as a singer, in an interview with us on July 24, 2017, through Facebook’s Messenger, Maíra Baumgarten explains her motivation to create the group:

My immediate motivation was to think

that I wouldn’t have the radio that has

always accompanied me and that I consider one of the best (among the few

good) radios in Brazil. On the other

hand, I knew that the extinction of these organs

was strategically inadequate in terms of state planning

and action and that, possibly, this proposal was based on political interests of reduction of the state and concealed economic

interests (in physical areas, areas of activity, among

others). As a singer and actress in the cultural scene of Porto Alegre, with projects such as

the Clube MPB, I knew the importance of these vehicles

to the area. Therefore,

I saw no way other than creating a movement

to defend these institutions and that would certainly be more

effective in social networks.

Thus in explaining her motivation, she makes her position clear against Sartori government’s public policies directed toward culture, which are actually economic in nature and not cultural, and also recognizes the role of digital social networks as agents of cyberactivism.

Finally, when specifically asked about the role of accountability exercised by the group Movement for the Preservation of TVE/ FM Cultura (“In your opinion, does the group function as an accountability agent, i.e., rendering accounts to society about policies which have been implemented by the government and culminated in the extinction of foundations?”), Maíra answers

I believe that as

soon

as it was created

(as it grew very fast)

the Movement even engendered news in

local newspapers; however,

the media is not interested in really connecting society and the state, let alone disputing

political interests. On the other hand, their own political interests (and in

spaces, market, etc.) ...

influence their publications, so I believe

that spaces in social networks

have been much more effective

in mediating between society and state

departments that develop

policies and activities directly (or even indirectly, as in the

case of research and inspection institutions) focused on the

population and on the satisfaction of social needs and interests. Recently, when the government

decided to change the programming

of FM Cultura radio

(including international pop and de-characterizing Brazilian music programs and journalism

programs), we created an event in the group focused on the debate of the topic. More than

two thousand people

showed interest and participated in the event, which also had

an enormous number of shares, leading to an intense debate

on the theme in social networks.

She explained that the group was created with a clear objective of exercising the right to communication, and so it is believed that the group can be characterized as an agent that tries to bring a balance between state, public, and private broadcasting to the scenario of media, historically devoid of public-type actors. Because the extinction of TVE/FM Cultura, Rio Grande do Sul’s main public broadcasting system, was not being denounced by the private media and its own journalistic programs were being discontinued, she found on Facebook the space to do it. Thus in this case, Facebook was used as a medium to force the government to be accountable by demanding to keep their campaign promises that included preserving TVE/FM Cultura.

Interpreting Research Data: The Group’s Posts

In order to analyze the participation of the public in the Facebook group Movement for the Preservation of TVE/ FM Cultura, all the posts between December 14, 2016, and June 30, 2017, were selected. This period was chosen because it precedes in a week the date of the vote that approved the extinction of the foundations by the Legislative Council of Rio Grande do Sul, according to the package of changes presented by the state government. (The group is still active and the analysis was interrupted by the end of June due to the deadline for submission.)

During the analyzed period, a total of 352 posts were counted, with the majority concentrated in the month of December 2016, when the group had 132 posts, representing 37.5% of the total. It is evident that this period produced more publications due to the proximity of the date of the vote of the package, even though it was not analyzed for the whole month. We observed in these postings a predominance of people supporting the movement and criticizing the state government, thus mobilizing an attempt to pressurize the state representatives not to approve the extinction of the foundations.

In the analysis, we classified the posts in 25 categories separated by the predominant subject of the post, which, after quantification, were reduced to the following 10 main categories, in addition to the category “others”: (1) support to the movement; (2) criticism of the government; (3) news/ reports; (4) cultural diffusion; (5) invitation for protests/ manifestations; (6) unavailable attachment 4; (7) trade unions; (8) Sofia Cavedon’s newsletter; (9) criticism of journalists/ media; (10) inquiries.

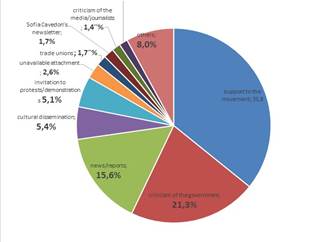

After the categorization of all the posts made during the analyzed period, we made a chart to visualize the percentage per category and to compare the topics that led the public to publicly manifest in the group. Figure 1 shows the categories separated by color, next to the percentage of posts reached by each category in relation to the total.

Figure 1. Posts separated by categories (percentage)

Source: made by the author.

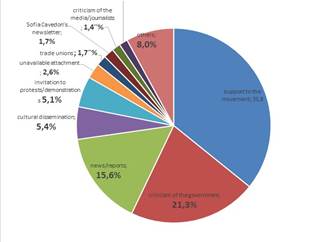

As shown in Figure 1, the category “support to the movement” obtained 35.8% of the posts, representing the largest volume of publications. It includes posts with long texts written by the members of the group, replicas of newspaper columns, and the simple use of hashtag #SalvesalveTVE/FMCultura (#saveTVE/ FMCultura). This category includes those posts that support both the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura and the broadcasters directly, such as praise to the broadcasters or the Piratini Foundation. We also included videos sent by artists from the Brazilian’s cultural scene, such as the duo Kleiton and Kledir and messages sent by political figures such as the former minister of culture Ana de Hollanda (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Message from the former minister of culture

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura. Available at

The category “criticism of the government” has the second highest number of posts (21.3% of the total). The criticism here were in majority made over the state government, but criticisms of the municipal and federal governments were also made here, for example, the analyses of experts concluding that the economy alleged by the state government as justification for the extinction will be very insignificant. Also, people already dissatisfied with the government used this space to reinforce their positions with the publication of hashtags #forasartori and #foratemer (#sartori_ out and #temer_out). In the meme highlighted in Figure 3, the “root” (authentic) governor is Brizola, while Sartori is “Nutella” (forged, simulated).

Figure 3. Category “criticism of the government.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The third most recurrent category was “news/reports” (Figure 4), with 15.6% of posts, which mainly included news related to the extinction of the foundations. This category was created because we realized that many posts did not contain a content produced by a member of the group, but links to news, articles, and reports of diverse vehicles of the great media as alternative vehicles. Thus, the content of these posts was not considered for its categorization and all of these were classified as “news/ reports.”

Figure 4. Category “news/reports.”

Next, “cultural dissemination” (Figure 5) comes across as the fourth most frequent category, with 5.4% of posts. It is relevant to highlight that this category is the most frequent among those that do not relate directly to the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura. These included posts that promoted musical shows, presentations, serenades, and other cultural events. It is important to remember that the cultural events organized with the purpose of supporting the movement were counted in the category “support to the movement.”

Figure 5. Category “cultural dissemination.”

Source:Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The category “invitation to protests/demonstrations” (Figure 6) accounted for 5.1% of the posts and refers mainly to manifestations of support to the Piratini Foundation. Also included in this category are the publicizing of acts/shows and protests and mobilizations motivated by other interests, such as an invitation to mobilize for direct voting for the President of the Republic.

Figure 6. Category “invitation to protests/manifestations.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

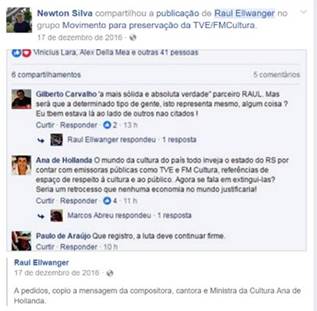

The “unavailable attachment” category was created because these types of posts occurred repeatedly in the group, reaching 2.6%. Because we did not have access to these posts, it was not possible to categorize them. Figure 7 shows the message: “This attachment may have been removed, or the person sharing it may not be allowed to share it with you.” We believe that these were posts from external links that were removed from their original pages because we had followed this group as a simple reader, manifesting only through “likes” in the posts, and had seen the attachments when these posts were made.

Figure 7. Category “unavailable attachment.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The “trade unions” category (Figure 8) was created to gather the various trade unions’ publications related to the professionals of the Piratini Foundation and that were shared in the group by several people. This category includes news and external links that brought relevant information to the employees of TVE/ FM Cultura, especially regarding the actions that the Union of Journalists of Rio Grande do Sul has been doing to mediate the relationship between employees and the state government.

Figure 8. Category “trade unions.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

With the same percentage of posts, there is the category “Sofia Cavedon’s newsletter” (Figure 9), which was created based on the posts that the city councilor herself, who is a member of the group, shared to publicize her actions in the political scenario (she was elected as a state deputy in October 2018). Figure 9 shows the link of the blog that she maintains to inform the public about her agenda and her projects.

Figure 9. Category “sofia cavedon’s newsletter.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The ninth most frequent category, “criticism of the media/ journalists” (1.4% of posts), matters particularly to this paper since it deals with the criticisms that members make of the mainstream media and of some journalists. This category can be considered a form of media accountability, also functioning as an observatory, a space in which the public can criticize and ask the media to play the role of media in a democratic society, that is, to monitor and have a critical attitude in relation to the government. The post shown in Figure 10 exemplifies this finding:

Figure 10. Category “criticism of media/journalists.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The last category to be considered, “inquiries” (Figure 11), also reached 1.4% of posts and refers to questions that members of the group post about the continuity of broadcasters and about what will be done with the programming.

Figure 11. Category “inquiries.”

Source: Facebook page of the Movement for the Preservation of TVE/FM Cultura.

The other posts, which appeared less frequently, were grouped in the category “others”, and included publications of happy holidays during the year and some tributes related to International Women’s Day.

During this research we realized that public’s great participation in the movement seems to be demonstrating the ideas of Bertrand (2002) that the media should be controlled only by message processors and the public. On the other hand, although Facebook is not a public broadcasting system, we believe that in such a case it acts as such because it allowed the public to have a voice in that scenario. That is, it allowed the public to exercise the right to communication, as Ramos explained (2005).

Final considerations

Going back in our research hypothesis, we verified through the data collected that the posts of the Movement for the Preservation of TV/FM Cultura indicate both the exercise of cyberactivism by the group and its accountability function. These posts not only disseminated information to almost 7000 followers on the extinction of TVE and FM Cultura, but multiplied protests, criticisms, news and positions in both the private media and also in the social network platforms through countless shares.

Internal sources5 have revealed that TVE/FM Cultura’s new management team has announced that the broadcasters will not be extinguished; they will rather have a “new management model,” directly linked to Governor Sartori’s Office. In practice, this is to transform public communication bodies, which have the function of guaranteeing the right to communication, in state-type broadcasters. This means that TVE/FM Cultura will eventually become mere propagators of state messages and could work as project of government interlocution with the society that provides more publicity of the political parties interests than the publicity of information, culture, and entertainment.

In this sense, sources reported that hitherto unable to file dismissals of public workers (still in rounds of negotiations conducted by the Tribunal Regional do Trabalho da 4a Região), the current administration has been silencing them, replacing career officials in the presentation and management of the radio programming grid by professionals hired in the outsourcing model. These are paid, naturally, by the society from which the government said it wanted to remove the burden of maintaining TVE and FM Cultura. Such a situation will require, in our view, a long life continuation of the Movement for the Preservation of TV/FM Cultura, whose cyberactivism has been fulfilling important functions in the sense of accountability and the right to communication.

Among the current developments of the case in the group’s posts, there is a report on the recommendation of the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the Public Ministry of Accounts for the government to suspend the termination of TVE and the Piratini Foundation. The justifications to support this recommendation is the fact that broadcasters, when commanded by the state, would risk political, ideological, and artistic censorship. This means that according to the configurations provided for in the Brazilian constitution, they would lose their characteristics of public broadcasters to become state broadcasters at the service of politicians in power and not of citizens.

The government did not comply with the recommendation and maintained the extinction of the foundation, published in a decree in the official journal of May 30, 2018. With this decision, the people of the state of Rio Grande do Sul lost a cultural agent, a media free of political and lucrative interests and its possibilities to demand government accountability. However, Sartori lost the reelection in October 2018 and the government changed, keeping TVE/FM Cultura still on, but with a fewer team and programs. We believed that cyberactivism was, in this case, effective in at least postponing this extinction decision, which, until June 2019, has not yet been defined.

Therefore, we can say that Facebook groups can be considered immensely useful tools to increase people’s ability to embrace cyberactivism. Despite being a private company and despite denunciations of technology censorship via algorithms pointed out by both Brazilian right and left wings, we could even go on to say that Facebook acted as a hybrid type of broadcast system that brought public interests before private or state ones and allowed people to use it to secure their right to communication.

Footnotes

1 According to Ramos, the "first-generation" civil rights refer to personal freedom, freedom of thought, religion, assembly and economic freedom; "second-generation" political rights include freedom of association in parties and voting rights; and the social rights, or "third-generation" rights, concern the right to work, care, study, and health care (Ramos, 2005, p. 245--246).

2 On December 21, 2016, by about 24--28 votes, the Legislative Council of Rio Grande do Sul approved Sartori’s government package that indicated the extinction of eight state foundations: Piratini, Zoo-Botanic, Economics and Statistics, Human Resources, Metropolitan and Regional Transport Planning, Cientec (Sciences and Technology), Gaúcho Institute of Tradition and Folklore (FIGTF), and State Foundation for Agricultural Research (Fepagro).

3 Group available at <https://www.facebook.com/groups/793536650682242/> Accessed in July 20, 2017.

4 This category refers to posts that are unavailable for viewing and may not be listed in other categories. It could be an error in the Facebook system or even some form of censorship, as suggested by some comments in the posts.

5 We have chosen to keep these sources confidential because they are Foundation employees and there is already a precedent of a lawsuit filed against a server because of the opinions he/she had expressed on Facebook.

References

Agência Nacional De Direitos Da Infância. (2007). Mídia e Políticas públicas de comunicação. Brasília: ANDI.

Bertrand, C. J. (2002). O arsenal da democracia: sistemas de responsabilização da mídia. Bauru: EDUSC.

BBC Brasil. (13 outubro 2016). Os 10 empresários mais ricos do mundo do setor de tecnologia. 13 ou.2016. http://www.bbc.com/ portuguese/geral-37648604

Carvalho,G.(2016).MídiapúblicanoBrasil:doestatalaonão-comercial. Ação midiática, n.11. https://revistas.ufpr.br/acaomidiatica/article/ download/42709/28469+&cd=2&hl=pt-BR&ct=clnk&gl=br

Fontcuberta, M. (1993). La noticia: Pistas para percibir el mundo. Barcelona: Paidós.

Forbes. (March 5, 2019) The richest people in the world. https://www.forbes.com/billionaires/#45df99b5251c

Lemos, A. (2003). Cibercultura: Alguns pontos para compreender a nossa época. In Lemos, A; Cunha, P (orgs.) Olhares sobre a Cibercultura. Porto Alegre: Sulina, 2003. p. 11--23. http://www. facom.ufba.br/ciberpesquisa/andrelemos/cibercultura.pdf

Levy, P. (1996). O que é Virtual. São Paulo: Editora 34. Levy, P. (1999). Cibercultura. São Paulo: Editora 34.

Maia, R. C. M. (2008). Visibilidade Midiática e deliberação pública. In: Gomes, W.; Maia, R. C.M. Comunicação e democracia: problemas e perspectivas. São Paulo: Paulus.

Malini, F., & Antoun, H. (2013). A internet e a rua: ciberativismo e mobilização nas redes sociais. Porto Alegre: Sulina.

McQuail, D. (1997). Accountability of media to society: Principles and means. European Journal of Communication. Vol. 12, No. 4, p. 511—529.

O’Reilly, T. (s.f.). What Is Web 2.0: Design Patterns and Business Models for the Next Generation of Software. <http://www.oreilly.com/pub/a/web2/archive/what-is-web-20.html?page=1>.

Paulino, F. O. (2010). Responsabilidade social da mídia. In: Christofoletti, R. (Org.). Vitrine e vidraça: crítica de mídia e qualidade no jornalismo. Covilhã: LabCom Books. http://www.labcom-ifp.ubi.pt/ficheiros/20101103-christofoletti_ vitrine_2010.pdf

Peruzzo, C.M.K. (2005). Internet e democracia comunicacional: entre os entraves, utopias e o direito à comunicação. In: José Marques de Melo e Luciano Sathler. (Org.). Direitos à comunicação na sociedade da informação. São Bernardo do Campo: UMESP, , v. 1, p. 267--288.

Ramos, M. C. (2005). Comunicação, Direitos Sociais e Políticas Públicas. In Marques , J., & Sathler, L. Direitos à comunicação na Sociedade da Informação. São Paulo: UMESP.

Recuero, R.(2009). Redes sociais na internet. Porto Alegre: Meridional.

Romais, A. (2001). Mídia, democracia e esfera pública. In: Jacks, N. Tendências na comunicação. Porto Alegre: L&PM.

Wolton, D. (2004). Pensar a comunicação. Brasília: UnB.