Investigación e innovación

Class of framing the war on drugs in the media of northern Mexico: the cases of Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale

Clase de encuadre en la guerra contra las drogas en los medios de comunicación del norte de México: los casos de Bar Sabino Gordo y Casino Royale

Classe de enquadramento da guerra às drogas nos meios de comunicação do norte do México: os casos de Bar Sabino Gordo e Casino Royale

Revista Mediaciones</

Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios – UNIMINUTO, Colombia

ISSN: 1692-5688

Periodicity: Semestral

vol. 15, no. 22, 2019

Received: 05 October 2018

Accepted: 20 March 2019

Published: 20 June 2019

Abstract: The purpose of this article is to describe how and to what extent the attacks on Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale were framed by the northern Mexican media: El Norte and Milenio Diario. Framing theory is used to contextualize and discuss how these events were represented. Discourse and content analysis of 224 news items produced immediately after the attacks and subsequently carried out. The results suggest the idea of class distinction as a backdrop to the drug war phenomenon in Mexico. While the event at Casino Royale was intensely discussed by the news and the amount of images was greatly increased, news about Bar Sabino Gordo was mainly published on the front pages of the newspapers in question. The victims at the Casino Royale were hardly mentioned, attention was focused on the appropriation of the site, while the people killed and wounded at Bar Sabino Gordo were framed as victims of their own decisions to be there.

Keywords: Framed classes, discourse analysis, national press, Monterrey, quantitative content analysis, war on drugs in Mexico.

Resumen: El objetivo de este artículo es describir cómo y hasta qué punto los ataques a Bar Sabino Gordo y Casino Royale fueron enmarcados por los medios de comunicación del norte de México: El Norte y Milenio Diario. La teoría del framing se utiliza para contextualizar y discutir la forma en que se representaron estos eventos. Análisis del discurso y de contenido de 224 noticias producidas inmediatamente después de los ataques y poster a ellos se elaboró. Los resultados sugieren la idea de distinción de clase como un encuadre posterior del fenómeno de la guerra contra las drogas en México. Mientras que el evento en Casino Royale fue discutido intensamente por las noticias y la cantidad de imágenes fue mucho mayor, las noticias sobre Bar Sabino Gordo se publicaron principalmente en las portadas de los periódicos en cuestión. Las víctimas en Casino Royale casi no se mencionaron, la atención se concentró en la apropiación del sitio, mientras que las personas muertas y heridas en Bar Sabino Gordo fueron encuadradas como víctimas de sus propias decisiones de estar allí.

Palabras clave: Encuadre de clase, análisis del discurso, prensa doméstica, Monterrey, análisis cuantitativo de contenido, guerra contra las drogas en México.

Resumo: O objetivo deste artigo é descrever como e até que ponto os ataques ao Bar Sabino Gordo e Casino Royale foram reportados pela mídia do norte do México: El Norte e Milenio Diario. A teoria do enquadramento é usada para contextualizar e discutir como esses eventos foram representados. Análise do discurso e do conteúdo de 224 notícias produzidas imediatamente após os ataques e posteriormente realizadas. Os resultados sugerem que a distinção de classe funciona como pano de fundo para o fenômeno da guerra as drogas no México. Enquanto o evento no Casino Royale foi intensamente discutido pelos noticiários e a quantidade de imagens aumentou muito, as notícias sobre o Bar Sabino Gordo foram publicadas principalmente nas primeiras páginas dos jornais em questão. As vítimas do Casino Royale não foram mencionadas, a atenção se concentrou na apropriação do local, enquanto as pessoas mortas e feridas no Bar Sabino Gordo foram enquadradas como vítimas de suas próprias decisões de estarem lá.

Palavras-chave: Enquadramento, análise do discurso, imprensa nacional, Monterrey, análise quantitativa de conteúdo, guerra às drogas no México.

Introduction

In 2006, the government of Felipe Calderón adopted a state policy against the production, distribution and trafficking of illegal drugs within Mexican territory; this policy was called by the media the “War on Drugs”. While it was a novel policy for contemporary Mexico, it was not far from the state policy originated in the United States in the 1970s by then President Richard Nixon (Fischer, 2006) of direct combat against drug traffickers; it was not a reconsideration of the issue in terms of public policy. Since Felipe Calderon announced a frontal assault on traffickers, expectations of street violence increased and confrontations between state forces and traffickers significantly increased at different times and places.

This “War on Drugs” was used by different news media to report on the violence arising from smugglers and federal forces on the streets, with the situations being framed according to where the confrontations took place. Bar Sabino Gordo was a public bar located in the heart of Monterrey, the capital city of Nuevo León. It was regularly visited by people from the working class. On July 8, 2011, drug traffickers entered the venue, shooting and killing 20 people and injuring five more. Casino Royale, on the other hand, was a place where local inhabitants from the upper and middle classes would gather and play on gambling machines since its opening in November 2007. On August 26, 2011, a group of criminals and drug smugglers burnt it out, killing 52 civilians and wounding dozens more.

This study describes how and to what extend the attacks on Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale were framed by two local newspapers, El Norte and Milenio Diario. The specific research questions of this study are about how intensely these events were discussed in these newspapers, what messages the photographs in the newspapers conveyed about the events, and where the news stories about these events was located in the newspapers. This study is based on scholarly discussion of framing theory: individual frames (Alasuutari, 2004; 1999; D’Angelo, 2002; Entman, 1993; Gamson, 1989; Goffman, 1986; Scheufele, 1999; Winter, 2008), media frames (Flores & Quiroz, 2011; Flusser, 2001; Grillo, 2007; McCombs & Ghanem, 2001; Weaver, McCombs, & Shaw, 2004; Teun A. Van Dijk, 1988; s.f.; 2008), and class framing (Derné, 2008; Keeton & Scheckner, 2013; Kendall, 2011).

The contribution of this paper to the literature in the field is to analyze the framing of class distinction throughout the content of the abovementioned newspapers. Journalism studies have intensively discussed the framing manners and processes of daily news in the context of racism, immigration and the “War on Terror” (Entman, 1991; Fernández, 2013; Igartua, Cheng, Moral, Fernández, Frutos, Gómez-Isla & Otero, 2008; Liebes, 1992; Lind & Salo, 2002; Norris & Kern, 2003; Semetko & Valkenburgh, 2000). This research report discusses the framing of news from the perspective of social class1 as a subsequent theme reinforced and triggered by the War on Drugs in Mexico (Miranda & Iglesias, 2015).

The following is a description of the sections that comprise this paper. The “Theoretical Framework” section discusses the roots and contemporary studies of the frame analysis. This particular approach provides an opportunity to examine the evident differences in the way and frequency in which an event is reported by different sources; thus, the ideas and studies discussed here are connected to the frame analysis of the events in question in this paper. The “Data and Methodology” section details the sample and analysis techniques to provide a glimpse into how the study was conducted. Newspapers’ names, time-spans and number of paragraphs are also mentioned in order to explain the scope of this inquiry. The “Results” section presents the answers to the general and specific research questions mentioned before. In “Conclusions”, there is a discussion of the results from a theoretical perspective, considering the ideas and studies mentioned in “Theoretical Framework”.

Theoretical Framework

The framing approach is conceived in various ways (D’Angelo, 2002; Scheufele, 1999; Winter, 2008). Examples are individual frames, media frames, and class framing. Individual frames refer to the manner in which different scholars discuss the dimensions and characteristics of their production and use by individual people. Media frames, on the other hand, are tentatively linked to the daily life of the people. These frames are subsequently divided into discourse and image framing. Class framing, finally, refers to the promotion and adoption of a particular way of life from the media content to the audience. It has typically been analyzed in its cinematic expressions (Derné, 2008; Keeton & Scheckner, 2013) but has been identified in newspapers too (Kendall, 2011). The main input of this paper is to unpack the idea that class distinction is promoted as a subsequent frame of the War on Drugs in the northern Mexican media. This section begins by describing some of the main insights of the frame definition.

Individual Frames

Erving Goffman (1986, p. 10) assumes that “…definitions of a situation are built up in accordance with principles of organization which govern events—at least social ones—and our subjective involvement in them”. Such definitions of a situation are what he calls “frames”. Thus, principles of organization and human involvement in them is what he is keen to identify in the daily life of society under this conceptual framework. This abstract but sophisticated description of the frame creates terrain where any particular element of the social world can be enhanced and understood, including the media. Newspapers, in that sense, are considered major definers of the contemporary world: they define situations, and the newspaper audiences are those involved in them. This framework helps us unpack and understand the principles of organization which govern events reported in newspapers.

Although news stories can be framed in accordance with the principles of organization of newspapers, a frame originates in both the principles of organization of newspapers and of journalists, because both get involved with the coverage of events. Alasuutari (2004; 1999) suggests that principles of organization are related to norms and rules imposed by certain institutions and, specifically, with the personal frames and identities of individual people. Thus, certain criteria are imposed by newspapers’ institutions on their journalists regarding their daily activities. However, journalists have personal frames and identities which also shape their work. Therefore, a collective identity can also be discussed because, in fact, the final end of institutional norms and rules is the creation of a collective identity by conceiving the legitimation of its members. News stories, in that sense, are built not only on the principles of organization of the newspaper and its journalists but also on the principles of organization of the journalists themselves.

Thomas (2007) identifies eight different2 players shaping the world globally. Among them are the global media which, as an institution, frames the world it portrays. Weaver, McCombs and Shaw (2004) suggest that the content of news media can be typified on three different levels —issues, attributes and opinions—which correspond to objects, framing and actors, respectively. A frame, under this typology, is what McCombs and Ghanem (2001) then describe as an affective attribute of an object that corresponds to news content and people’s thoughts.

Gamson (1989) investigates those principles of organization from the perspective of culture. This scholar argues that, although the prominence of competing frames is embodied in sponsoring enterprises and media organization and practices, there is a sort of cultural resonance which is expressed in news content that is manifest and latent. Thus, although it is true that journalists belonging to their newspaper’s corporation which shapes the content of the information, nevertheless, the cultural background the society to which they belong—better understood as cultural narratives and myths— also affects the content of the news. According to Van Dijk (2008), there is a certain link between citizens, media as an institution, and politicians, which supports Gamson’s idea of the importance of the cultural environment or background. This link is evident in the way citizens adopt and produce new ideas using media content.

Grillo (2007) is concerned with place of the participant public and style of reporting within the news construction. In a comparative study on the presence of the public in the construction of the news in Argentina, Brazil and Chile, the public in the Argentine news has a more notable incidence than in the news of the other countries. For example, 70% of Argentine news constructed the news with the presence of the public as a source of information in contrast with 38% in Brazil and 45% in Chile. Based on Charaudeau’s typology (2003) and empirical evidence, Grillo (2007) suggests another typology he terms “spaces of the public”: public external space, internal space of interpretation, and the relationship of the two. It is thus hypothesized that the public on screen is constructed by the media as an articulation strategy between reality, its construction by the media, and the public.

In Scheufele’s process model of framing research (1999), a constant ongoing procedure is proposed in which media and audience interact in three different stages: inputs, processes and outcomes. In this ontological process, frames are built by journalists in response to media organizations’ commands, suggesting the diffusion of ideologies and attitudes throughout the media messages to their audience. The audience then transforms these attitudes and behaviors, and journalists as audiences are those responsible for transporting these frames back to the media organizations.

In contrast to Scheufele’s model, that of Norris, Kern and Just (2003)3 suggests that news frames are embodied by the event itself, the government frame, and the frame of the group involved in the news. All are preceded by a sort of social culture and followed by public opinion and a policy agenda, which then goes back to the social culture. In between this process, there are the real world indicators, personal experience and interpersonal communications.

Although both models have similar elements, each describes the framing process and focuses its attention on different elements. Scheufele’s model (1999) pays attention to how frames are originated by media organizations, no matter how strong the demand of the audience in terms of changing the frames characteristics. This model suggests the reinforcement and dominance of media organizations.

On the other hand, the model of Norris et al. (2003) reduces the influence of media organizations and pays more attention to the way in which news frames are shaped by institutions and society. In this case, public opinion and policy agendas have an important role in the constitution of news frames.

Media Frames

Over more than 20 years, many scholars have investigated how news framing is manifested and linked to the daily life of people, particularly to the discourse and image framing configuration and relationship between media content and society. In the following, some of these studies are discussed in order to contextualize this research. Entman (1991), for instance, studies the way in which U.S. international news framed the shooting down of Korean Air Lines (KAL) Flight 007 by a Soviet fighter, and of Iran Air Flight 655 by the U.S.S. Vincennes. Entman suggests that, while KAL victims are humanized verbally and visually in the press, the Iran Air victims are less portrayed and, as a consequence, are “…less likely to evoke empathy…” (p. 15); thus, the Iran Air event was mostly considered from a technical angle. Liebes (1992), in another study, analyzes the way the Intifadeh and Gulf War are covered by U.S. and Israeli television news. Even though this study is based on a cross-national comparison, it constitutes an antecedent to analyzing the frames used by news media because it provides a clear distinction in the way that each news national source reported the different events. Liebes suggests six different ways in which these events were covered: excising, sanitizing, equalizing, personalizing, demonizing and contextualizing.

In another study, Semetko and Valkenburg (2000) identify frames in press and television news about European politics. They found five different frames: the attribution of responsibility, the conflict, economic consequences, human interest, and morality. In subsequent studies, Rodero, Pérez and Tamarit (2004), Leon (2012) and Morera (2012) measure these frames in different contexts. Rodero et al. (2004) studied Semetko and Valkenburg’s frames in the context of the attack of March 11, 2004 on radio station SER, while Leon (2012) focused his attention on the study of these frames in the Spanish press about the Gibraltar dispute. In another study, Morera (2012) analyzes these same frames in how Spanish news discussed the US-led military operation Desert Storm.

Lind and Salo’s (2002) study is not related to the representation of news events but it is concerned with politics. This inquiry describes an evolution of how topics such as feminists and feminism are framed in US television. Although it is based on representations of feminists and feminism, women’s representations were used to compare the frequency in which each issue appeared on air. According to these scholars, feminists and feminism appear rarely and are represented as demonized, yet they are less often portrayed as victims, more often have agency, and are regularly “…associated with public sphere activities including media/the arts and politics” (p. 211).

Igartua et al. (2008) focus their attention on the way in which immigration into Spain is framed in the news. They are particularly concerned with positive and negative consequences as framed by the national press. In this study, they identify that the press positively frames immigration as an economic contribution but are disturbed by increases in delinquency. Moreover, they suggest that certain nationalities are judged either positively or negatively by Spanish public opinion. For example, Latin Americans are positively accepted, while Moroccans are judged badly by Spain’s public. Fernandez (2013), in other study, is also concerned with frames in the Spanish press. According to this scholar, there are coincidences and divergences in the frames used by the newspapers El País, El Mundo and ABC. Their positions on racism in sport and homosexuality all coincide, yet they all differ in matters of ideology, politics and religion.

Flores and Quiroz (2011) and Flusser (2001), on the other hand, suggest that a frame can be analyzed as an image as well. In this case, these scholars identify three different moments: the concrete world, the traditional, and technical images. The latter are abstractions of the third degree, abstracting texts from traditional images that have been abstracted from the concrete world. Technical images, in that sense, are produced by devices, and are distorted by human perception. These devices can be a conventional camera, a computer or a cell phone, all capable of presenting a misconstruction of the concrete world.

Class Framing

Class framing in the media seems to be a phenomenon rarely investigated. Few scholars who discuss this issue identify the conditions through which class framing is manifested and is adopted by particular audiences. Derné (2008), for instance, comments on the way that the middle class in India adopts consumerist practices but also a cosmopolitan vision throughout the media. This scholar argues that not only cinematic but also satellite television content reinforce the practices of the middle class, which originate in a cultural ideology of consumerism from the transnational capitalist class. In this sense, the media frame of class promotes the idea that an elite status is rooted in consumption and transnational movement, which the middle class then adopts and consolidates in their daily life practices.

In another investigation, Keeton and Scheckner (2013) also find a strong connection between film content and the socio-cultural background in the USA after the Vietnam War. In this interconnection, these scholars describe how a social movement—such as antiracism and anti-sexism—was first linked to the economic issues of social class in order to narrow the gap between white and black family incomes. These social movements then inspired the production of independent films opposed to the Vietnam War and economic conditions at home. Although it is not emphasized, independent films frame a class condition in which the main motive is a demand by the lower classes to institutions through the representation of their daily socio-cultural environment on the big screen.

Kendall (2011) identifies a variety of journalistic and media frames for the upper, middle and working classes. For instance, the upper class is framed in both a positive and negative manner. The positive frames are consensus, admiration, emulation and a price tag, whereas the negative frames are sour grapes and bad apples. The consensus frame is when the wealthy are portrayed as normalized, like everyone else. In the admiration frame, the wealthy are seen as generous and caring people. The emulation frame is evident when wealth personifies the “American Dream”, the general aspirational goal of all immigrants to the US. The price-tag frame is when the wealthy are represented as believing in materialism over any other doctrine. Negative frames of the upper class are sourgrapes and bad apple. The sour-grapes frame is when the wealthy are depicted as unhappy and dysfunctional, while, in the badapple frame, wealthy people are scoundrels and criminals.

On the other hand, the working class is also framed in a positive and a negative way. Negative frames are shady framing, caricature framing and fading blue-collar framing, while heroic framing is positive. Shady framing is when workers are portrayed as greedy or as part of unions and/or organized crime. Caricature framing mostly refers to the working class represented as servants and under submission to white people; they can be either television’s buffoons, bigots or slobs. In fading blue-collar framing, the working class is depicted as unhappy at work or out of work. The only positive frame identified for the working class is heroic framing, when the media represents the working class as protagonists of a particular event, or as victims whose life was taken in place of another, so that people pay tribute to them.

Media representations of the middle class are in the form of middle-class-values framing, squeeze framing and victimization framing. Middle-class-values framing refers to the way in which the media standardizes middle class values as the only ideals for all people of the nation-state, including the upper and working classes. These values are normally taken as aspirational by the working class; the upper class rarely sees them as models to follow. In squeeze framing, the middle class is depicted in the fine line between their lifestyle cost and their capacity to pay for it. Victimization framing refers to the way in which the middle class is portrayed as a victim of the upper and working class’ activities, which greatly endanger the middle-class way of life.

Data and Methodology

This investigation of the journalistic treatment of the events related to the attacks on the Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale led us to employ quantitative content analysis (Krippendorff, 2004; Riffe, Lacy, & Fico, 2005) and discourse analysis (Fairclough, 2003). The information was obtained from the two morning newspapers with the largest circulation in the city of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon: El Norte and Milenio Diario. The former prints 127,136 copies daily and is owned by Grupo Reforma, whereas Milenio Diario distributes 45,353 copies daily and is part of the Multimedios organization (INE, 2014).

In order to give equal attention to both events considered in this study, it was decided to devote a month’s span of coverage for analysis, from the time when the first news story appeared in each of them. Therefore, the analysis of events related to Bar Sabino Gordo began in both newspapers from July 9, 2011 and concluded on 9 August, whereas coverage of the incident involving Casino Royale went from August 26 to September 26, 2011.

The study looked only for news stories related to both events, leaving out newspaper columns and comments or letters to the newspapers that had to do with only one of the cases. Qualitative aspects considered were the location and size of the news, as well as the phrases that accompanied the presentation of the facts in the newspapers’ contents. Attention was particularly focused on the frame and contextualization of the news.

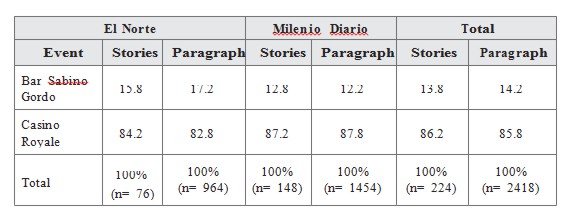

There is a strong difference in the proportion of news stories produced by the newspapers El Norte and Milenio Diario. El Norte reported 76 news stories with 964 paragraphs compared to 148 news stories with 1454 paragraphs for Milenio Diario (See Table 1). Nevertheless, there is no implication in this difference of itself for the frame analysis carried out here, because it does not tell us much about the characteristics of those news stories in both sources. When the proportion of news stories is contextualized in terms of the number of paragraphs by event, the difference persists yet it emphasizes the event at Casino Royale.

Results

Although both newspapers report that the events at Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale related to the War on Drugs, there are certain frames which distinguish the way in which each presents the information, because each of them emphasizes or focuses its attention on different matters. The general question addressed by this paper relates to the frames these local newspapers used in referring to these particular events. Despite the fact that the event at Casino Royale was intensively discussed by these newspapers and the amount of images displayed by them was larger, the event at Bar Sabino Gordo seems to play a more important role in the journalists’ agenda because the news stories about this latter event are located slightly more toward the front pages of these newspapers than the news about Casino Royale.

How deeply are the events of Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale treated on the newspapers in question?

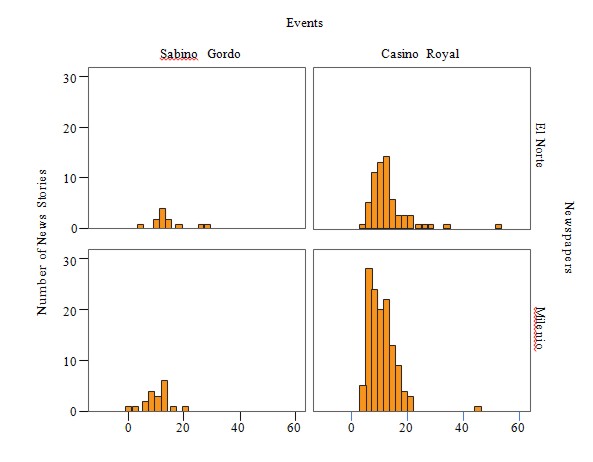

The proportion of news by paragraphs is similar for both events, yet the number of news stories is bigger for the event at Casino Royale (See Figure 1). Regarding the event at Bar Sabino Gordo, more than 80% of the news—25 out of 31—is more than seven paragraphs long, compared to 75% of news—141 out of 193—being more than seven paragraphs long for the event at Casino

Royale. These figures suggest that, whereas the information regarding Casino Royale is sufficient for constructing a precise explanation of the event, the information about Bar Sabino Gordo is scarce; thus, regarding this latter event, the newspapers seem to have constructed their own explanation of the event because there is insufficient information to assimilate different ideas and subjects’ positions.

Figure 1

SEQ Figura \* ARABIC 1: Histogram of number of paragraphs in news stories by newspapers and events.

Another frame which distinguishes how events were covered is the reasons that the newspapers in question gave for the attacks. 53.3% of news stories suggest “drug sale” as the main motive of the Bar Sabino Gordo incident, followed by 33.3% proposing a disputa de la plaza4 and 13.3% with adjuste de cuesta5 in the same vein. In the event at Casino Royale, on the other hand, 55.6% of the news suggested cobro de piso6 as the main cause for the incident, while the remainder of the news stories discussed “drug sale”, “reckoning”, “revenge against owners” and “revenge against authorities” in the same proportion (5.6%). The main causes that each of the media outlets suggested for the attacks suggest that there was already a sale of drugs by members of a drug cartel in Bar Sabino Gordo while, in Casino Royale, there were different cartels struggling with one another to gain the place.

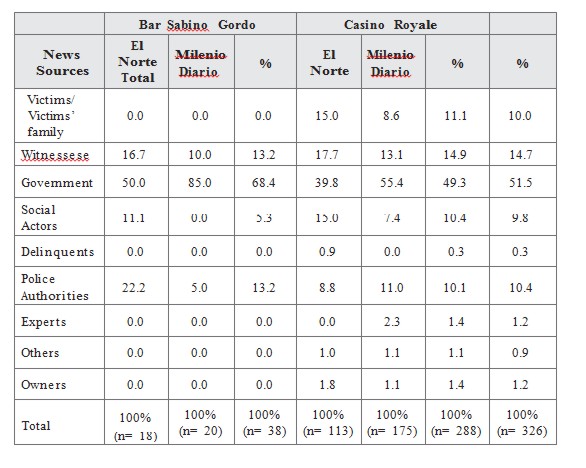

Another frame that also differentiates the way the events were covered by the media is the sources of the news stories. One source constantly mentioned in news stories regarding both events is “government” (51.5%), followed by “witnesses” (14.7%) and “police authorities” (10.4%). Bar Sabino Gordo victims are completely ignored as sources while those of Casino Royale are treated differently (11.1%). In many of the news reports of the latter event, the personal and emotional aspects of the victims were mentioned—for example, he/she was young, was a good person, was left in abandonment of his/her family, was very active, etc. (See Table 2).

The analysis of this content shows that 10% of the news stories referred to the victims at Bar Sabino Gordo as the cause of what happened to them and 45% regard the venue as negative. However, when it comes to Casino Royale, the news stories do not refer to the victims as guilty (only 0.5% do) nor the venue as negative (11%).

Finally, the total amount of news stories with exact figures in both newspapers is 132, of which 108 correspond to the event at Casino Royale whereas only 24 correspond to the incident at Bar Sabino Gordo. What is interesting here is comparing the total amount of news stories (n=224) with the proportion of those with accurate figures (n=132) for each event. When this information is seen in context, the percentages change and the proportions are modified mainly for the reporting of Casino Royale. The total amount of news stories about Bar Sabino Gordo is 31, of which 24 (77.41%) have exact figures. On the other hand, the total amount of news stories about Casino Royale is 193, of which only 108 (55.95%) have exact figures. This information implies that, even though there are fewer news stories about Bar Sabino Gordo, these have a high degree of accuracy in their figures. Statistical measurement (χ2 = (1, N = 132), p = 0.361, C = .563), nonetheless, suggests no relationship between the collocation of exact figures on news stories on these events and the editorial policy of newspapers analyzed.

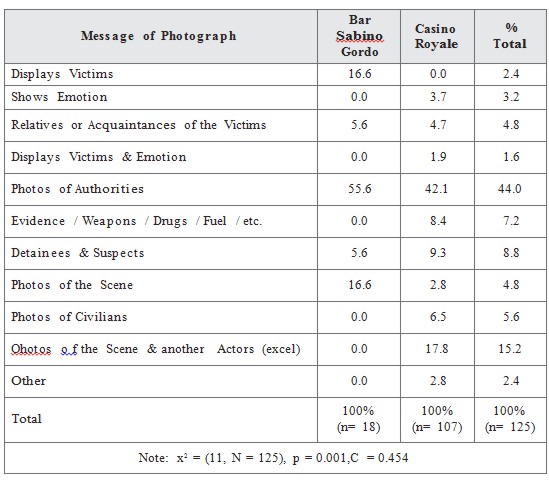

What do the messages of the photographs about the events display?

A visual frame that shapes the information and conveys a message are the photographs attached to the news stories. There are a total of 253 photographs, of which 12% are of Bar Sabino Gordo, while 88% are of Casino Royale. In the newspaper El Norte, 102 photographs were published, of which 13% were related to the event at Bar Sabino Gordo whereas 87% relate to Casino Royale. In Milenio Diario, 151 photographs were published, 12% of which related to Bar Sabino Gordo while 88% relate to Casino Royale. Regarding the number of photographs per news story, 83.3% of news about Bar Sabino Gordo has only one picture while the rest two or three. On the other hand, 77.5% of news about Casino Royale has only one photo, 8.5% have two, and the rest of the news stories have up to seven photographs.

The majority of photos in both events are of the authorities: 55.6% in the case of Bar Sabino Gordo and 42.1% for Casino Royale. News stories of this latter event also present photographs of evidence. In the case of Bar Sabino Gordo, the photographs also portray victims of the attack (16.7%) and the scene (16.7%). There are no images of victims at Casino Royale but there are photographs that portray emotionality (3.7%), relatives or acquaintances of the attack’s victims (4.7%) and the scene (2.8%). In addition, photos of Casino Royale also display detainees and suspects (9.3%) and evidence, weapons or drugs (8.4%). In the case of Bar Sabino Gordo, there are no images of detainees but a few of civilians (6.5%) (See Table 3).

Location of the news stories of the events in question in the newspapers

The number of photographs devoted to the event at Casino Royale, along with the number of paragraphs, reinforces the intensity with which this event was covered by the media in question. Nonetheless, the figures regarding the location of the news stories inside the newspapers’ sections suggest the importance that the event at Bar Sabino Gordo had for journalists. Since both are events which involve a large set of contemporary themes such as drug trafficking, gambling and bar regulations, and the killing of innocent people, they are mostly published on the front pages of newspapers in the period of time in which the events occurred and immediately after (for two or three months).

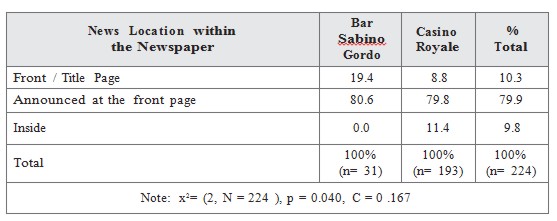

In the case of Bar Sabino Gordo, 80.6% of the reports were published on the front pages, followed by 19.4% which are completely narrated in the same newspaper section. However, 79.8% of news of Casino Royale was on the front page of the newspapers in question, followed by 11.4% placed on the inside sections and 8.8% reported completely on the front page (see Table 4). What is interesting here is that the amount of news stories located on the first pages is greater for the event at Bar Sabino Gordo than for that at Casino Royale, suggesting that Bar Sabino Gordo played a bigger role or had a slightly greater importance for the newspapers.

Conclusions

At the beginning of this paper, a research question was elaborated to study how and in what proportion the events at Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale were framed by local newspapers, El Norte and Milenio Diario. Although these events are quite similar in scope and in the magnitude of their civil consequences, they differ in the kind and amount of characteristics on which newspapers focus their attention while reporting their news stories. These results suggest class distinction as a subsequent frame for the War on Drugs7 in the northern Mexican media. The relevant characteristics by their respective percentage found in this inquiry are: number of paragraphs; causes of the events; news sources; news stories with accurate figures; messages of the photographs; location of the news in the sheets or sections of the newspapers.

Frames in the northern Mexican media in reporting the cases of Casino Royale and Bar Sabino Gordo are generally positive for the upper and middle classes and negative for the poor and working classes. Congruent with Kendall (2011), in the case of Casino Royale, the consensus frame is used to construct news stories about the wealthy or upper class and normalize their human condition in relation to everyone else in a positive way. What is interesting here is that the newsdoesnot use negativeframes—for example,sour-grapes—when referringtowealthypeople,eventhoughtheywerecaughtandtrappedin a casinowhilethe eventoccurred.Moreover,victimizationframingwasused toreportnewsstoriesaboutthe middleclassinthe CasinoRoyaleevent,the killedandwoundedpeopleatthatsite beingconsideredcollateralvictimsof the actionsofcriminalorganizations.

On the other hand, the murdered and injured people at Bar Sabino Gordo are reported as victims of their own circumstances. Although Kendall (2011) talks about a heroic framing to describe working-class heroes and victims in a positive manner, in the event at Bar Sabino Gordo, murdered and injured people are mentioned as victims but in a negative way because they are reported as victims of their own circumstance of being in that venue.

The information coverage for both events used the government as the main source and, in a few cases, the public. Although the presence of the public in news is an articulation strategy to maintain a relationship between media and the public, in the cases of Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale its presence is discrete: what is considered as the public, “victims”, are at second place as a source and immediately after municipal and state authorities, consistent with Mexico and globally. Contrary to Charaudeau (2003) and Grillo (2007), the main priority of news in these events is not the public. Perhaps the nature of the events and the authorities’ demands of the media contravened the hypotheses of these scholars.

According to the model of Norris, Kern and Just (2003), news frames are shaped by institutions and society embodied in a sort of social culture. The socio-cultural context, in the case of Monterrey8, has its roots in a class stratification imposed by the Spaniards soon after the invasion9. The results of this inquiry support the idea of a class distinction as a frame in the northern Mexican media, fed mainly by institutional perspectives of the War on Drugs phenomenon. Teun A. Van Dijk (n.d., p. 198) suggests that the majority of citizens mostly depend on the media to be informed, yet the media depend on politicians when constructing their news stories. This is not the exception in the events at Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale, where it is evident that the news stories are framed by municipal and state authorities.

What is interesting is the difference in the framing of one or another authority, depending on the event and the place of the victims seen by the media in both events; both matters clarify the state of dependence discussed by Van Dijk. Soon after the attack on Bar Sabino Gordo, the “municipal authorities” were demanded by the newspapers to clarify the motive of the event and respond for the victims. On the other hand, in the case of Casino Royale, the “state authorities” were demanded to regulate this and other casinos in the state and to respond to the victims’ families as well.

In both events, municipal and state authorities were the main resource for journalists constructing news stories, placing the “victims” and the “victims’ family” as second in importance.

Attacks were reported according to the place, Bar Sabino Gordo or Casino Royale. Even though the cases analyzed here are domestic, compared to the Intifadeh and Gulf War (Liebes, 1992) or the shooting down of the KAL and Iran Air flights (Entman, 1991), in both Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale there are distinctions in how information is reported. While Bar Sabino Gordo is basically depicted as a dispute by different crime organizations or drug smugglers for the sale of illegal drugs, Casino Royale is framed as a location where the drugs had already been on sale. Additionally, information coverage is scarce for Bar Sabino Gordo but abundant for Casino Royale (see Table 1 & Figure 1).

Another frame that reinforces this distinction is the kind of victims in each other event. The places attracted different kinds of people with different motives, according to news information in both newspapers. The messages describing the facts of these two events suggest that victims at Bar Sabino Gordo are, in a way, guilty of what happened to them because they went to this venue. It is a place where drugs are sold and is, therefore, disputed by criminals. The description given of them is without family context. Beyond being considered as victims, they are not referred to again during the time span of the reporting of the event. This is in contrast to what is described about the event at Casino Royale, where the victims are almost absent and facts are presented as the consequences of an attempted takeover of the venue by criminals. The culprits are state or municipal authorities but not the victims, who were, on the other hand, good people, most of them family members. In each other event, the responsible subject position is changed, depending of the place.Finally, even though it is true that the technical images prevaricate the concrete world, as suggested by Flores and Quiroz (2011) and Flusser (2001), the newspapers’ images regarding the events at Bar Sabino Gordo and Casino Royale frame concrete world, reproducing the events but in a partial manner. In these cases, the issue is not that newspaper images are substitutes for the concrete world but that they frame the world and convert the irrelevant into the relevant, sensationalizing the situations (Lozano, 2004; Thussu, 2007).

References

Alasuutari, P. (1999). Rethinking the Media Audience. London: Sage.

D’Angelo, P. (2002). News Framing as a Multiparadigmatic Research Program: A Response to Entman. Journal of Communication, 870–888.

Derné, S. (2008). Globalization on the Ground. Media and the Transformation of Culture, Class, and Gender in India. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications Inc.

Entman, R. (1991). Framing U.S. Coverage of International News: Contrasts in Narratives of the KAL and Iran Air Incidents. Journal of Communication,41(4), 6–27.

Alasuutari, P. (2004). Social Theory and Human Reality. London: Sage.

Charaudeau, P. (2003). El discurso de la información. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Entman, R. (1993). Framing: Towards Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing Discourse. Textual analysis for social research. New York: Routledge.

Fernández, M. (2013). La diversidad y la discriminación en encuadres El País, El Mundo y ABC. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periódistico, 19(1), 91–106.

Fischer, G. (2006). Rethinking our War on Drugs. Connecticut: Praeger.

Flores, P., & Quiroz, P. (2011). El poder de la imagen en la sociedad de control. Faro(13), 118–130.

Flusser, V. (2001). Una filosofía de la fotografía. Madrid: Editorial Sintesis.

Gamson, W. (1989). News as Framing. The American Behavioral Scientist, 33(2), 157–161.

Goffman, E. (1986). Frame Analysis. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Grillo, M. (2007). El público en los noticieros televisivos. Conexão – Comunicação e Cultura, 6(11), 123–138.

Igartua, J.–J., Cheng, L., Moral, F., Fernández, I., Frutos, F., Gómez–Isla, J., & Otero, J. (2008). Encuadrar la inmigración en las noticias y sus efectos socio–cognitivos. Palabra Clave, 11(1), 87–107.

INE. (2014). Catálogo Nacional de Medios Impresos e Internet 2014. Recuperado el 22 de Junio de 2015, de Instituto Nacional Electoral: http://www2.ine.mx/archivos2/DS/recopilacion/JGEor201401– 24ac_01P04–01x01.pdf

Keeton, P., & Scheckner, P. (2013). American War Cinema and Media since Vietnam. Politics, Ideology, and Class. New York: Palgrave MacMillan.

Kendall, D. (2011). Framing Class. Media Representations of Wealth and Poverty in America. New York: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, INC.

Krippendorff, K. (2004). Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology. London, United Kingdom: Sage Publications.

León, G. (2012). El contencioso de Gibraltar como conflicto mediático. Estudio de los encuadres noticiosos en la prensa española. Estudios sobre el Mensaje Periodístico, 18(2), 531–540.

Liebes, T. (1992). Our War/Their War: Comparing the Intifadeh and the Gulf War on U.S. and Israeli Television. Critical Studies in Mass Communication, 9(1), 44–55.

Lind, R., & Salo, C. (2002). The Framing of Feminists and Feminism in News and Public Affairs Programs in U.S. Electronic Media. Journal of Communication, 211–228.

Lozano, J. C. (2004). Infotainment in national TV news: A comparative content analysis of Mexican, Canadian and U.S. news programs. Annual Conference of International Association for Media and Communication Research. Porto Alegre: IAMCR/ AIERI.

McCombs, M., & Ghanem, S. (2001). The Convergence of Agenda Setting and Framing. In S. Reese, O. Gandy, & A. Grant, Framing Public Life (pp. 67–81). London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Miranda, O., & Iglesias, A. (2015). ‘Agenda–setting’ de medios en la guerra contra las drogas. Estudios sobre el mensaje periodístico, 403–420.

Morera, C. (2012). Operación “Tormenta del desierto”: guerra y encuadres noticiosos en la prensa Española. Razon y Palabra, 79.

Norris, P., & Kern, M. (2003). Framing Terrorism. The News Media, the Government and the Public. New York: Routledge.

Riffe, D., Lacy, S., & Fico, F. (2005). Analyzing Media Messages. London, United Kingdom: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Rodero, E., Pérez, A., & Tamarit, A. (2004). El atentado del 11 de marzo de 2004 en la Cadena SER desde la teoría del framing. ZER, 14(26), 81–103.

Scheufele, D. (1999). Framing as a Theory of Media Effects. Journal of Communication, 103–122.

Semetko, H., & Valkenburgh, P. (2000). Framing European Politics. A Content Analysis of Press and Television News. Journal of Communication, 93–109.

Thomas, G. (2007). Globalization: The Major Players. In G. Ritzer, The Blackwell Companion to Globalization (pp. 84–102). Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Thussu, D. K. (2007). News as Entertainment. The Rise of Global Infotainment. London: Sage Publications.

Van Dijk, T. (2008). News, Discourse, and Ideology. In K. Wahl–Jorgensen, & T. Hanitzsch, The Handbook of Journalist Studies (pp. 191–204). London: Routledge.

Van Dijk, T. (1988). News as Discourse. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Van Dijk, T. (n.d.). Discurso y racismo. Persona y Sociedad, 191–205.

Weaver, D., McCombs, M., & Shaw, D. (2004). Agenda–Setting Research: Issues, Attributes, and Influences. In L. Kaid, Handbook of Political Communication Research (pp. 257–282). London, UK: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Winter, N. (2008). Dangerous Frames. How Ideas about Race and Gender Shape Public Opinion. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Notes